stranger than paradise

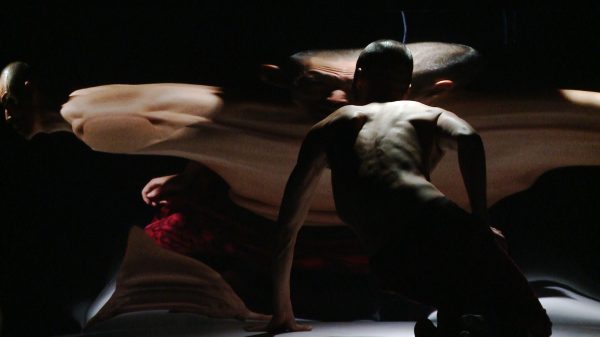

Stranger Than Paradise, vaguely associatively linked to Jim Jarmusch’s wintery Eighties road movie, is a genuinely film-choreographed work: a hybrid, subtly futuristic chamber play for eight people and an investigative camera. Almost hesitantly, the view approaches “from outside”, as it were, from an imaginary auditorium, the erratic actions of the performers, soon developing a pull that is otherwise difficult to produce on the stage. The concave mirrors are a key to this work, the flowing images they produce aim at melancholy and eeriness. Stranger Than Paradise, set in sunken moods and deceptive images, is an elegy that marks the transition from one species to the next, is a reflection of the systematic expansion of human capacities into the mechanical, the animalistic, and sometimes the “monstrous” mixed animal-human existence into it.

The choreographic film-project Stranger Than Paradise was published as video-on-demand in co-operation with Tanzquartier Wien.

Still / Stranger Than Paradise was presented as a combined evening of live-performance (Still) and film (Stranger than Paradise) at ImPulsTanz Vienna Int. Dance Festival 2021.

The body is a obsolescent model; it is still needed, but the preparations for its abolition are in progress, which evokes melancholy and farewell manoeuvres. The old utopia of the equality of beings is hidden in the sphinxic shimmer of the dancers. Dealing with the humanimal raises questions of division and duplication. Is the image that the mirror produces an addition or a division? Does it share the view that is presented or is it simply duplicated? Modification and infection are closely related: we are bio-machines, electronically improved, but biologically endangered. Only technologization, the synthesis of flesh and mechanics can secure us: The illusion of the human, which its perfectly reproduced surfaces can generate, conceals the artificiality of the new species. We will get used to them – that is, to ourselves.

Stefan Grissemann

moments of ultimate beauty

Notes Regarding Stranger Than Paradise by Liquid Loft

by Stefan Grissemann

With every dance step, humanity also advances, barely noticeable, but consistently. Mankind looks back, relates to what has been and at the same time it moves forward. It is no coincidence that the art-historical references are just as decisive in the choreography of Stranger Than Paradise as is the latent futurism in the images, the figures, their drifting, their tics. Time is out of balance here, it appears boldly compressed, yet surprisingly re-developed and unfolded.

Liquid Loft’s productions of the past two years update each other: The former Stand-Alones who only work with themselves are now moving closer together, albeit avoiding any contact; they glide silently past one another, only partially facing each other. The inner logic that they follow is a future one, the pathos of their bodies dampened by the serenity they are programmed for: fluid, fleeting characters, swaying in step, frozen in pain as if behind cold glass.

The images of the individuals, undissolved between animals, humans and machines, melt gently in the concave mirrors. Their surfaces generate illusions, do not throw back or reject, but rather invite people to pass through, to transit. Lewis Carroll’s Alice ends up in her Wonderland by going through the reflector, and also Jean Cocteau’s youthful poet in Le sang d’un poète falls into the abyss of a disturbing parallel world after jumping through the surface of the mirror-ocean. Behind the reflector lie opposite worlds, the unexpected, the preconscious. Illusion is merely the other side of “reality”, distortion the only way to recognizability.

In the improvisational run-through of costumes and disguises, the desire for flexible, or if you will: liquid identities becomes clear. The colors glow, but the bodies are threatened to disappear behind them (as in the mirrors), to adapt, to blend in until they are invisible. The textiles help to keep changing directions, they assist with the desired course (and self-) corrections. In the sober white of the stage, the ensemble seems to be blurred: out of focus. The mirror shares emotions (and communicates them), but remains completely stoic itself. It doesn’t set a focus, acts egalitarian, because everything is equally valid in him. The actors, who loll in front of the distorted surfaces, blur into one another.

Stranger Than Paradise allegorically melts transhumanism and the pandemic into one another: The human body can be touched and technologically expanded; everything that we call consciousness takes place in the networks of our brains. It is available for upload to other data carriers. Our deficient human bodies are technically enriched by implants and prostheses, elevated to cybernetic organisms. The merging of man and machine, which was celebrated by the band Kraftwerk in 1978 in their electro classic, transfers the godlike ideal of existence imagined by Nietzsche a century before into the age of robotics (“Man machine, semi human being / Man machine, super human being”) . The Übermensch from back then is transformed into über-androids, because Homo sapiens has disqualified himself and gambled away his alleged wisdom. Suggestions for its improvement are on the table: The next level of being human lies in a computer-aided new solidity (and solidarity) of body and mind. The techno-optimism that underlies the “spiritual machines” of Google futurist Ray Kurzweil, however, has this dark opposite side: Human self-disempowerment taking place before our eyes accompanies the automation of intelligence, the simulation of creative thinking.

Stranger Than Paradise, set in sunken moods and deceptive images, is an elegy that, in a slowed-down configuration, marks the transition from one species to the next, and it is a reflection of the systematic expansion of human capacities into the mechanical, the animal, and sometimes the “monstrous “of a mixed animal-human existence. A series of cryptic poses, which in this work are carried out like secret agreements, form the prelude to a play of magnetism and fluctuation.

Artificial intelligence, which is modeled on the natural but was designed to go beyond it at any time, will lead to the establishment of a new ethic that non-machines are demonstrably incapable of. The self-learning, cognitive apparatus that we put to our side make algorithmic decisions based on an incorruptible but highly problematic morality that chooses the lesser evil in any life-threatening situation. Whoever wants to save has to make sacrifices. The responsibility for the triage is delegated to the machine. It was eventually programmed to think for itself. That sounds paradoxical: self-determination being prescribed, autonomy required, and freedom being fastened. The structural contradiction that is found in this and the compulsion to achieve higher and higher levels of efficiency have made those who will replace humans very tired. Their ennui is tangible, but it throws off moments of ultimate beauty.

The separation of body and feeling is almost impossible to achieve, although the risk of a permanently changeable identity radically undermines physical stability, even as it produces increased euphoria: I can be anything, including an object! The human development thrust once propagated by Friedrich Nietzsche inevitably leads, when viewed from the present, into an artificial cosmos, into machine art, into a Second Life that offers new “realities” and virtual identities.

In paradise everything would seem strange (if only because it is so far away), but behind the liquid mirrors and beyond the anthropo-logic, strangeness is a wild understatement.

Breitenseer Lichtspiele

Diagonale Festival des Österreichischen Films, Graz, AT

Diagonale Festival des Österreichischen Films, Graz, AT

Stuttgarter Filmwinter

Animatter media art Victoria, BC (CAN)

Light Moves Festival of Screendance, Limerick, IE

Light Moves Festival of Screendance, Limerick, IE

ImPulsTanz Vienna International Dance Festival, AT

ImPulsTanz Vienna International Dance Festival, AT

Theaterfestival Spectrum, Villach (AT)

Tanz.Ist Dornbirn, AT

Tanz.Ist Dornbirn, AT

Tanz.Ist Dornbirn, AT

Tanzquartier Wien, AT

Tanzquartier Wien, AT

Tanzquartier Wien, AT

dates

Dance, Choreography: Luke Baio, Stephanie Cumming, Dong Uk Kim, Katharina Meves, Dante Murillo, Anna Maria Nowak, Arttu Palmio, Hannah Timbrell

Artistic Direction, Choreography: Chris Haring

Video Production, Camera: Michael Loizenbauer

Sound Concept, Composition: Andreas Berger

Light Design, Scenography: Thomas Jelinek

Camera: Kurt van der Vloedt (Artvan)

Costumes: Stefan Röhrle

Production Design: Liquid Loft

Theory, Text: Stefan Grissemann

Stage Management: Roman Harrer

Distribution: sixpackfilm

International Distribution Stage Performance: APROPIC – Line Rousseau, Marion Gauvent

Production Management: Marlies Pucher

Production: Liquid Loft

Music arranged by Andreas Berger. Additional, rearranged music by Penelope Trappes – The Hair Shirt, Eurythmics – Aqua. A production by Liquid Loft in cooperation with Tanzquartier Wien. Liquid Loft is supported by: Kulturabteilung der Stadt Wien (MA7) and Bundesministerium für Kunst, Kultur, öffentlichen Dienst und Sport (BKMÖS).

credits

vorarlberger nachrichten, 27.03.2021

Tanz ist-Festival von Günter Marinelli bereichert jedenfalls schon das Heimkino / Brisant und ein ästhetisches Erlebnis

Dornbirn 100 Besucher bei einer Aufführung, die vor 20 Uhr beendet ist, sind seit zehn Tagen in Vorarlberg zugelassen. Die dazugehörende Verlautbarung ist gut zwei Wochen alt. Ein internationales Tanzfestival, wie es der Spielboden jährlich zwei Mal bietet, ließ sich so nicht programmieren. Günter Marinelli hat früh genug umdisponiert. Der Tanz ist-Macher streamt keine Aufführung, er übermittelt Projekte, die als digitale Produktion entstanden sind. Seit Freitagabend ist „Stranger than Paradise“ der österreichischen Performancegruppe Liquid Loft von Chris Haring und Stephanie Cumming online.

Tänzer bleiben im Fokus

Inspiriert vom gleichnamigen, von Melancholie gezeichneten Roadmovie von Jim Jarmusch ist ein Kammerspiel zu erleben, in dem acht Personen zwischen Selbstbeobachtung und -bewunderung den Kontakt zum anderen scheinbar nur zum Selbstzweck suchen. „Wir sind Biomaschinen, elektronisch verbessert, aber biologisch gefährdet“, heißt es im Text zur Produktion. „Stranger than Paradise“ bietet ein ästhetisches Erlebnis, bleibt im Bildcharakter bei dem, was man am Ensemble so schätzt und enthält weitere inhaltliche Brisanz, wenn man Selbstentfremdung entdecken kann. Grundsätzlich zeigt die Produktion aber auch das Ausschöpfen technischer Möglichkeiten, das dort aufhört, wo die einzelne Tänzerin und der einzelne Tänzer nicht mehr im Fokus stehen. Das heißt viel.

die presse, 30.01.2021

Liquid Loft online: Monströse Körper, opulenter Tanz / Isabella Wallnöfer

Bis Sonntag online: die neue Choreografie von Chris Haring. Cool.

Donnerstagabend hatte “Stranger Than Paradise”, das neue Stück von Chris Haring für seine Company Liquid Loft, auf der Plattform des Tanzquartiers online Premiere. 72 Stunden lang ist es nun abrufbar – bis Sonntagabend. Auch wenn einiges stören mag an einer rein virtuellen Begegnung mit diesen beeindruckenden Tänzer-Charakteren (zum Beispiel die Tatsache, dass man nicht selbst entscheiden kann, was oder wen man in den Fokus nimmt) – es lohnt sich, denn ein intensives Erlebnis ist es allemal. Am besten: Kopfhörer auf, laut aufdrehen und eintauchen in diese fremde, zeitweise bizarre Welt, in der es von Wesen wimmelt, die nicht immer menschlich sind, sondern auch animalisch zucken und die Pfoten heben oder sich zu fließenden Gebilden verformen . . .

Cool wie Jim Jarmuschs gleichnamiges Road-Movie, das atmosphärisch Pate stand, sind hier Musik, Setting und Tänzer, die teilweise von Haute-Couture-Auftritten inspiriert scheinen. Auf der weißen Bühne posen sie vor gebogenen Spiegeln, die einzelne Körperteile völlig verzerrt wirken lassen und die Gestalten als groteske, wabernde Gebilde zurückwerfen. Dann wirken sie wie kauzige Einzeller unter dem Mikroskop – oder wie Aliens, deren übergroße Mäuler nicht nur nach Luft schnappen, sondern mit elektronisch bearbeiteter Stimme sehnsuchtsvolle Songs mitsingen oder unverständliche Texte flüstern, die leise aus einer anderen Welt herüberschwappen.

Am Ende kommt es zu einem kollektiven Räkeln, Kuscheldecken werden über die Bühne gezogen, nicht selten sitzt jemand in Modemagazin-Pose darauf. Man fühlt sich eigentümlich berührt von diesem opulenten, sinnlichen Moment. Dieses Stück, es ist wie ein Ausblick in eine Welt der Zukunft, in der alle Grenzen aufgehoben sind, nicht nur die der Geschlechter.

wiener zeitung, 30.01.2021

Mensch oder Maschine? / Verena Franke

Chris Harings „Stranger than Paradise“ zeigt, dass Performance auch online überzeugen kann.

Sind es Menschen oder Maschinen? Gar Cyborgs, also ein bisschen von beidem? Eine logische Entscheidung ist eigentlich gar nicht gefragt, sondern ein Auf-sich-wirken-Lassen der starken cineastischen Bilder, die Chris Haring und sein Ensemble Liquid Loft da auf den Bildschirm zu Hause bringen. „Stranger than Paradise“ heißt die Uraufführung, die bis inklusive Sonntag auf der Website des Tanzquartier Wien als Video-on-Demand kostenlos zu sehen ist.

Der heimische Choreograf Chris Haring hat sich vom gleichnamigen Independent-Roadmovie von Jim Jarmusch aus dem Jahr 1984 inspirieren lassen. Die Atmosphäre der darin vorkommenden drei verlorenen Seelen, die durch weite Landschaften wandeln, verwandelt Haring in einen bildstarken Performance-Film. Sein vielleicht bisher melancholischstes Werk in den 15 Jahren des Bestehens seines Künstlerkollektives Liquid Loft – ungewohnt tiefernst.

Bunte, glänzende und glitzernde Cyborgs

Ein Schwenk vom Zuschauerraum über die Technik hin zur weißen Bühne des Tanzquartiers lässt gleich zu Beginn erkennen, dass hier die Kameraführung nicht nur der Aufzeichnung einer Vorstellung im Guckkastenformat dient. Vielmehr ist die Kamera ein fixer Bestandteil der Choreografie und beweist in den ersten Minuten des kurzweiligen Stücks, dass Tanzprojekte in gestreamter Version sehr wohl funktionieren. Und wie! Sie können sogar zum Staunen bringen, wenn zu den acht außergewöhnlich präsenten Performern (Luke Baio, Stephanie Cumming, Dong Uk Kim, Katharina Meves, Dante Murillo, Anna Maria Nowak, Arttu Palmio und Hannah Timbrell) gezoomt wird. Und man sieht detailgenau ihre Bewegungen, die immer wieder, trotz Innehalten und Repetitionen, dennoch im Fluss bleiben: emotionslos, jeder für sich selbst, in sich selbst gekehrt. Sie sind bunt, glänzend, mit Tiermuster, glitzernd und geschlechtsunspezifisch gekleidet, auch hier ständig im Verwandeln. Dazu mischt Liquid-Loft-Urgestein Andreas Berger eine Klangkulisse zwischen Eurythmics und Penelope Trappes, die eine mystische, dann wiederum animalische, bald auch düstere Stimmung verbreitet.

Mit vielleicht eineinhalb Meter hohen Spiegelfolien, halbrund aufgestellt, und raffinierter Lichtregie (Thomas Jelinek) wird ein Spiel der Reflexionen und der Fantasie inszeniert. Dong Uk Kim räkelt sich dabei im für liquid-loft-typischen Lippensynchrongesang, entkörpert sein verzerrtes Spiegelbild erst zu einem Alien, dann zu einer bizarren menschlichen Hülle. Das Gesicht deformiert sich scheinbar schmerzvoll. Die Abstraktion dieser Bilder kennt keine Grenzen, versetzt den Zuschauer beinahe in einen tranceähnlichen Dämmerzustand. Ein abruptes Ende dieser Szene folgt, fast gruselig überbelichtet wird exerziert. Ein stetiger Wechsel zwischen hell und dunkel, Mensch und Nicht-Mensch. Weitwinkel und Zoom folgen in perfekt inszenierten ästhetischen Bildern. Dass Haring in seinen Arbeiten immer auch cineastische Einflüsse klar erkennbar gemacht hat, ist bekannt und schließlich auch Teil seiner choreografischen Handschrift. „Stranger than Paradise“ fasziniert als Gesamtwerk, in dem Tanz, Inszenierung, Musik, Licht und Kameraführung ineinanderfließen.

der standard, 30.01.2021

Betäubende Spiegel / Helmut Ploebst

Das Dilemma des virtuellen Körpers: Uraufführung von „Stranger Than Paradise“ der Wiener Tanzcompany Liquid Loft

Eine Gruppe bunt gekleideter junger Leute kommt zusammen, um ein Bild zu tanzen. Mit so präzisen wie lasziven Bewegungen zu verspielt sprudelnd bis dickflüssig wirkender Musik lassen sie ihre Körper in eine existenzielle Vorhölle treiben. Die Bedingungen, unter denen Stranger Than Paradise, das neue Stück der Wiener Company Liquid Loft, auf der Website des Tanzquartiers Wien zu sehen ist, verstärken diesen Eindruck noch.

Die Performance der vier Frauen und vier Männer fand in der Museumsquartier-Halle G statt. Damit die zeitversetzt gestreamte Choreografie ihr Publikum erreichen kann, braucht es zusätzliche Infrastruktur: Kamera, Schnittprogramm, Vimeo-Plattform, Veranstalterwebsite, Netzübertragung und Bildschirm. Ein Glücksfall: Gerade die zwischen Tänzer und Zuschauer geschaltete Technik macht Stranger Than Paradise zu einem künstlerischen Treffer. Einen wichtigen Schlüssel zum Erfolg liefern acht biegsame Spiegel im Stück. Spiegelungen zählen bekanntlich zu den ersten Bilderfahrungen der Menschheit. Und sie haben ihre Tücken.

Der Medienphilosoph Marshall McLuhan meinte 1964 in seinem Klassiker Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man, dass diese Erfahrungen narkotisierende Wirkung hatten. Immerhin ist der Name Narziss auf das griechische Wort „narkein“ zurückzuführen – und das bedeutet „betäuben“.

Diese Idee greifen auch die Liquid-Loft-Gruppe und ihr Choreograf Chris Haring auf. Wie hypnotisiert betrachten die Performer anfangs die Verzerrungen ihrer Spiegelbilder in den konkav gebogenen Spiegeln. Was folgt, ist ein Wechselspiel aus Benommenheit und Versuchen, sich dagegen zu wehren. McLuhan erklärte die Betäubung mit der berühmten These, Narziss habe sich am Ufer eines Teichs gar nicht in sich selbst verliebt. Vielmehr sei er dem Stress erlegen, den die bildhafte Erweiterung seines Körpers ausgelöst habe, und einer daraus resultierenden „Selbstamputation“ zum Opfer gefallen. Das passt wie angegossen zu dem bei Stranger Than Paradise mitgelieferten Textmaterial.

Darin ist vom „Transhumanismus“ die Rede und davon, dass heute „unsere defizitären Menschenkörper“ einerseits „zu kybernetischen Organismen erhöht“ werden, was andererseits zu einer „Selbstentmächtigung“ führt. Die Spezies Mensch kappt also ihre eigenen Körper. Dazu merkt McLuhan an: „Selbstamputation schließt Selbsterkenntnis aus.“

reviews

Taking the performance situation into account when contemplating the performative arts isn’t really an option these days. Premieres online instead of onstage, pieces on the screen, watching on the computer. After almost a year of “practice”, a democratisation among participants in online conversations can be achieved, provided the tools are configured accordingly. The psychological barrier to ask questions is easier to overcome; people tend to have fewer qualms about writing in a chat compared to shouting at the stage from an auditorium. And, apparently, it’s also easier to express praise and thanks that way. Of course, all of this is at the expense of actually being “present”: of seeing and hearing the dancers’ bodies, of feeling, smelling, hearing the other spectators’ bodies – none of this is possible.

Why this lengthy observation in the opening remarks? Stranger Than Paradise cannot begin without reporting on the conditions of its performance either. First, I see a stage, eight performers move about on it, warming up, rehearsing. The edge of the stage is visible, covered with clothes that will be changed during the piece and fabrics that will be used as part of the performance. This exterior is complemented by the recording equipment: camera, monitors, computer with editing software, sound and light mixing console. The beginning resembles an “establishing shot” in film: the scene is set, the context is established, mostly from a bird’s eye view, from above at an angle, too. After the cut, I’m genuinely closer to the action. And soon, guided by the camera and the director, I’m right in the middle of it. As I sit in front of my computer screen with good headphones – it’s dark outside – it actually feels like I’m watching a movie, all of a sudden. Which makes sense in the context of Liquid Loft’s practice of frequently conceptualising bodies as mediatised, and the act of performing as a practice defined by cinematic images, even a cinematic language. The music – the score – also adds to this effect. It establishes the atmosphere, among other things, it underlines the solos’ highlights. Through it and with it, the dancers drift into another (dream) world, are recovered again in the end and finally, after the music has stopped, they are left surprised, confused, perplexed and are released back into – well, where to exactly? Off-screen? Into reality?

The interim are 40 minutes’ worth of reflections on images of the body, images of people; on loneliness, and on the possibility and, at the same time, the impossibility of approaching one another in a community. Fluid beings rather than machines or robots manifest themselves, which is underlined by a stage set made up of medium-height concave mirrors. This house of mirrors that is a blend of Deleuzian actuality and virtuality – outside of which the individual can no longer conceive of itself (or so the theory goes) – contains infinitely deep sadness and melancholy. Because the exterior, the coming together of these individuals also has the capacity for rigidity, for stagnation. There is only a (very) vague hint of becoming. This “becoming” (animal, machine, post-human?) is also associated with exertion and suffering. An echo of ubiquitous neoliberal self-optimisation is palpable but isn’t the most pressing concern. This seems to be the constellations and possibilities of communication that don’t exist yet and have to be renegotiated. The pas de deux are performed side by side. The bodies as signs (of automatonism, animalism, humanity) replicate themselves by way of their gestures, repeatedly solidifying into an image, sometimes even into eerie shadows. The most touching moments are those that approximate a connection and, for a little while, achieve harmony.

After the end of the piece, with the credits still running, I can’t help but google the music and make some surprising discoveries: Penelope Trappes’ interpretation of Nick Cave and The Birthday Party is colder than ice; a slowed-down Annie Lennox suddenly sounds like 1970s soul and then again like David Bowie. Ultimately, this draws the attention back to the fluidification of a rigid concept of identity and the not yet exhausted possibilities of becoming. Despite the melancholy, the sadness about an uncertain future, there remains a feeling of happiness, a sense of being moved, that lingers.